Employing and amusing patients formed an important part of treatment at Friends' Asylum and other nineteenth-century mental hospitals. In the eyes of managers, superintendents, and physicians, activities like farming, sewing, riding, and reading distracted patients from brooding thoughts while engaging and strengthening their minds and bodies. When Friends' Asylum first opened, it prioritized labor over leisure. As the decades passed, the institution began to value diversions more, and after the Civil War games had mostly replaced work that contributed to the Asylum's domestic economy.

Occupational Therapy

Employment

Occupational therapy was important at all asylums run on moral treatment, but it was especially crucial in the early days of Friends' Asylum. The superintendent needed the patients to work on the farm and in the kitchen because the Asylum could not afford to hire enough help to run it without patient labor. Quite apart from the benefits to the Asylum, work was supposed to help the patients recover by engaging them mentally, socially, and physically. Experts such as Samuel Tuke of the York Retreat held that occupation helped to keep the mind “from its favourite but unhappy musings” while giving patients a self-confidence that promoted their restoration (52–53). Employment formed part of Friends' Asylum's domesticity as well; historian Patricia D'Antonio argues that working alongside their caretakers let the patients feel like they were a part of the Asylum's family (127). Men's outdoor labor also provided salubrious exercise and fresh air, benefits which led physicians later in the century to see employment as a way to promote health of both body and mind. When Friends' Asylum discharged six of its patients as “restored” in Seventh Month 1835, the institution's physicians attributed the high number of recoveries to air and exercise.

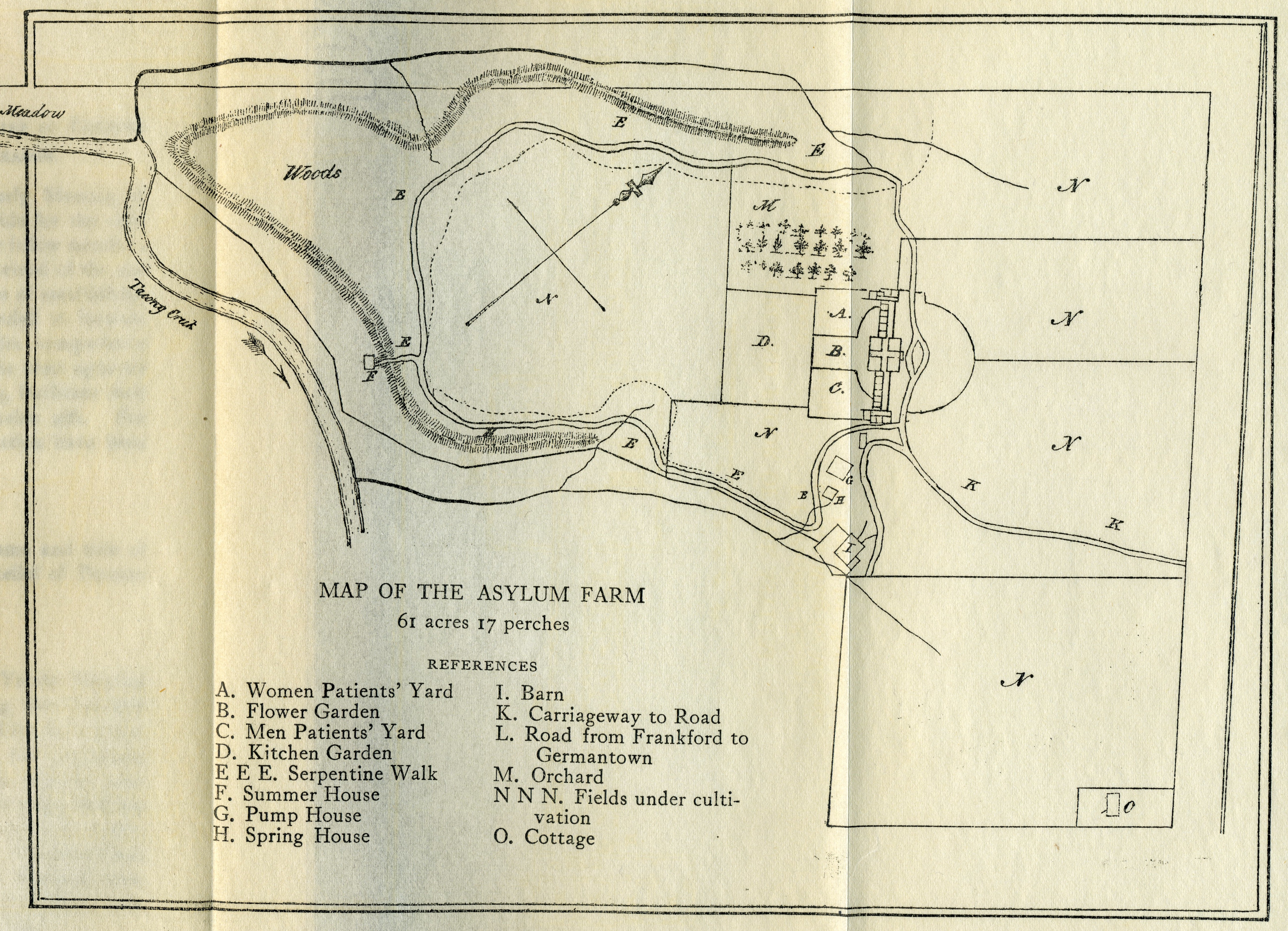

In Friends' Asylum's first few decades, the male patients helped to run the institution's farm and garden. They planted, plowed, cut wood, and hauled water, among other things. After the construction of a carpenter's shop and water pump in 1838, the men also pumped the Asylum's water and helped with woodworking projects such as the construction of fences (Seventh Month 1838; First Month 1840). While the male patients were helping outside the house, female patients sewed, knit, quilted, spun wool, did laundry, and cooked. Their jobs were equally important in running the Asylum, but gave them much less access to exercise and fresh air than the men's work outdoors, and received less attention in the superintendents' daybooks. However, the Asylum did recognize a need for air and movement in female patients, and often gave them first access to outdoor amusements. Whenever the carriage went out in Fourth Month of 1835, for example, it carried female patients, never men.

Patients were often reluctant to join their attendants in working. Superintendent Isaac Bonsall wrote that John Ha., one of the Asylum's first patients, was “so lazy that he [could] not be prevailed with to do work or to go out even to look at others” (Sixth Month, 23, 1817). Bonsall eventually resorted to punishing John with the shower bath if he did not work (Seventh Month, 23, 1817). Several decades later one of the Asylum's physicians described patient Hannah Po. in the same terms: “She can be induced only by threats of sh[ower] bath to sew a little now and then” (Casebook 5, p. 7). These difficulties help to explain why patient employment took a back seat to recreation later in the century. In an 1872 letter to his father, a young patient named William Ty. wrote, “I do not know much about the farm, as since I have been here, the patients have had no business in that line” (Ty.).

Amusement

Although Friends’ Asylum prioritized work over leisure during its first fifteen years, the institution did not shun recreation entirely. From the beginning, patients at the Asylum were in the habit of strolling a serpentine walk that wound through the grounds, going out on carriage rides with the superintendent, or playing ball. However, Friends’ Asylum began investing in patient recreation much more heavily in the 1830s, and many more leisure activities were available by the end of the decade. The appearance of other mental hospitals more successful in treating mental illness drove this push for amusements. When opened in 1817, Friends’ Asylum was one of only two institutions in the United States devoted exclusively to mentally ill people. By 1833, however, a number of other asylums had been founded, and many of them cured a far greater proportion of patients than Friends’ Asylum did (Spurzheim 151). The Asylum’s managers felt that their institution had not done all it could for its patients, and the board sought to reproduce the success of their peers by emulating those asylums’ focus on medical treatment and patient amusement (Third Month 1833). The board went so far as to write to several other asylums asking for advice on amusement and employment, and instituted many of the suggestions they received (Seventh Month 1835).

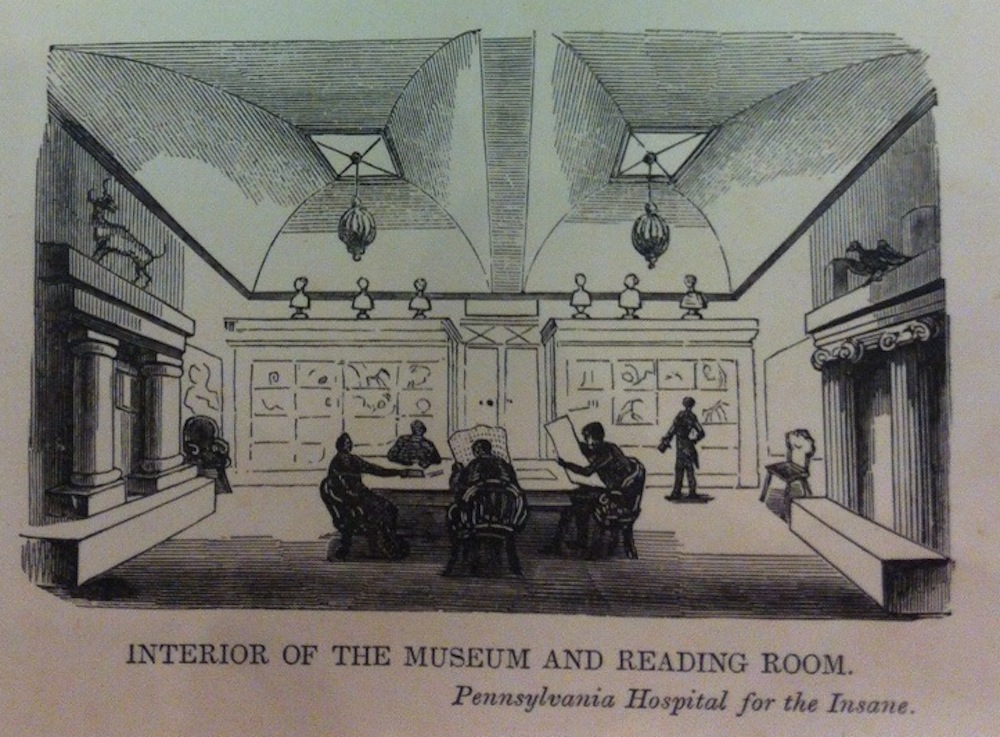

Outdoor diversions provided the same mental and physical benefits as work and received less resistance from patients, though they did not integrate the Asylum’s charges into a family structure in the same way employment did. Patients still walked about the Asylum’s grounds and took rides in the carriage, now driven by a coachman hired specifically for their excursions. They also played with lambs, rabbits, and poultry in their exercise yards, made use of a swing, and took part in quoits (a game similar to horseshoes). The physicians sometimes took patients fishing, and occasionally a manager would invite patients to his house for tea. If the weather was not suitable for going out of doors, patients stayed in their dayrooms and amused themselves by drawing, painting, or reading educational magazines. No matter the weather, convalescent patients went to the library to read books and examine specimens of natural history.

Friends’ Asylum also began encouraging its patients to engage in intellectual pursuits. By producing paintings or drawings, paying attention to lectures on chemistry, reading books of history, or practicing handwriting and arithmetic, patients demonstrated their ability to follow genteel social norms. In the eyes of physicians and managers, these activities helped patients recover by engaging them not with just any part of the world but with the rationality of nature as communicated through science or art.

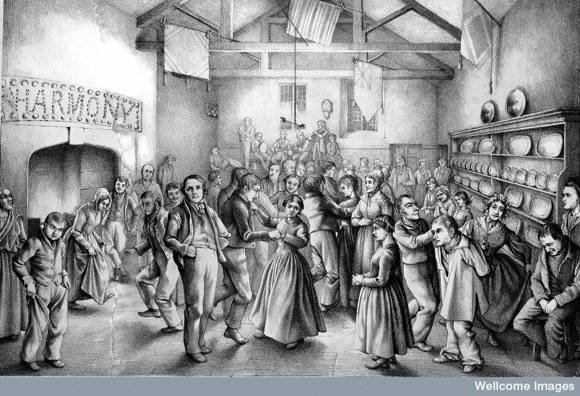

Friends’ Asylum continued to introduce further leisure activities throughout the remainder of the century. The 1860s saw an interest in games such as cricket, croquet, and (European) football. The asylum constructed a gymnasium and lecture hall in 1871, and a greenhouse in 1880. Because Quakers saw dances and stage-plays as frivolous and immoral, Friends’ Asylum does not appear to have offered these diversions, though they were common at other asylums (Reiss 7, 97).

Amusements at Friends' Asylum

Carriage Rides

Riding in the carriage was a prominent form of amusement that also provided light physical exercise. The coachman tried to engage patients’ attention by choosing interesting routes; the mental activity provided by this change of scene was thought to promote patients’ recovery. In addition to occupying the mind, riding helped strengthen the body and secure recovery from the physical disorders which physicians thought caused mental illness. The shocks and jolts of an early nineteenth-century carriage ride placed the activity among the ranks of “passive exercises.” These differed from active exercises in that the body was moved by outside forces rather than its own impulses; the exertion lay in maintaining one’s position. An educational magazine in 1837 concluded that carriage exercise was “very favourable to the re-establishment of convalescents who cannot yet take any active exercise,” because it “gives more vigour to the organs, without adding to the activity of their functions . . . and enjoys, in a very high degree, the advantages peculiar to passive exercises” (188). Similar effects on both mental and physical health were attributed to walking.

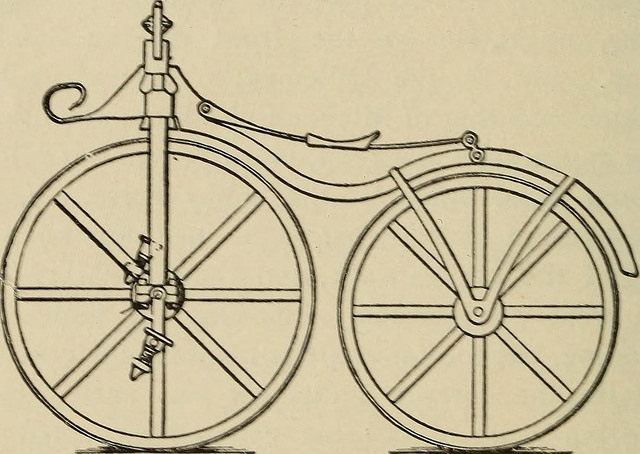

Velocipede

The most elaborate amusement Friends’ Asylum could boast before 1830 was an early bicycle known as a velocipede, which the Visiting Managers bought for the patients in June of 1819. The Managers’ promptitude in obtaining a velocipede is impressive, given that the velocipede had only been introduced to Philadelphia that spring (Herlihy 39-40).

Circular Railroad

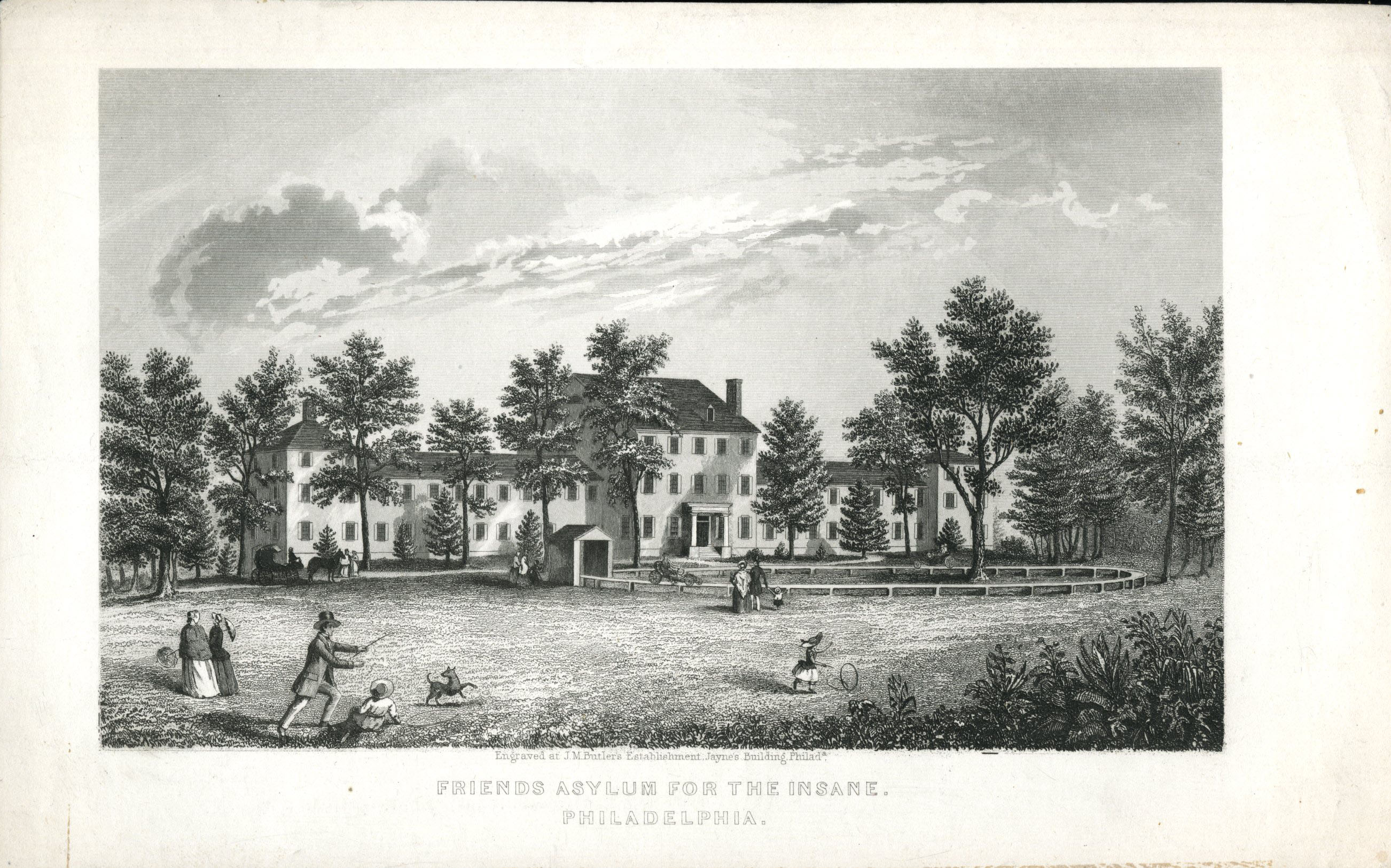

The most conspicuous diversion was the circular railroad introduced in 1835, which features in several engravings of the asylum’s facade. A letter from the Worcester State Lunatic Hospital inspired the railroad(Managers’ Minutes, First Month, 1835), and the managers modeled the device off of one that a Frankford Friend used to entertain his children (Seventh Month, 25, 1835). By pumping themselves around the tracks, patients got more strenuous exercise than they could riding in the carriage.

Animals

Among the diversions introduced in 1835 were lambs, rabbits, and poultry that the patients could play with in their exercise yards. In 1813 Samuel Tuke recorded that the exercise yards at the York Retreat were supplied with rabbits, poultry, sea-gulls, and even hawks (63). Asylum experts saw befriending animals as a way to revive patients’ social feelings. One member of the Pennsylvania Hospital’s staff wrote of the benefits of animals in a letter to Asylum managers: “I love to see a patient adopt some animate pet, if it be but a mouse, and would encourage the disposition; it has a humanizing and happy influence. Attention to animals gives the insane an occupation and an interest in something out of themselves and their delusions, whilst in their isolated situation it becomes a source of pleasure to feel that some creature is dependent upon them for its comfort, and perhaps in return loves them” (First Month 1835).

Lectures

On winter nights in the 1840s and 1850s, the Asylum’s physicians gave lectures for the patients on science and history. Public lectures on “useful knowledge” were popular in contemporary polite society, and other mental hospitals soon followed Friends’ Asylum’s example by instituting their own lecture series (Scott 792, Smith). By engaging them in “rational” topics, the physicians hoped to sooth patients’ minds. For example, the lectures given in the winter of 1858 examined Europe, the atmosphere, chemical affinity, electricity, and hydraulics, among other topics. The interest in science manifested itself in other ways as well; on one occasion, for example, Dr. Pliny Earle took some of the male patients to a museum in Philadelphia (Seventh Month, 17, 1841).

School

Friends’ Asylum also experimented with school classes for its patients in the 1840s. Beginning with the women in 1845, patients practiced their reading, writing, and arithmetic. Classes for the male patients were instituted several years later. The managers and physicians found that the classes, in addition to occupying patients’ time, helped them develop a sense of discipline and orderliness (Eleventh Month, 8, 1845).